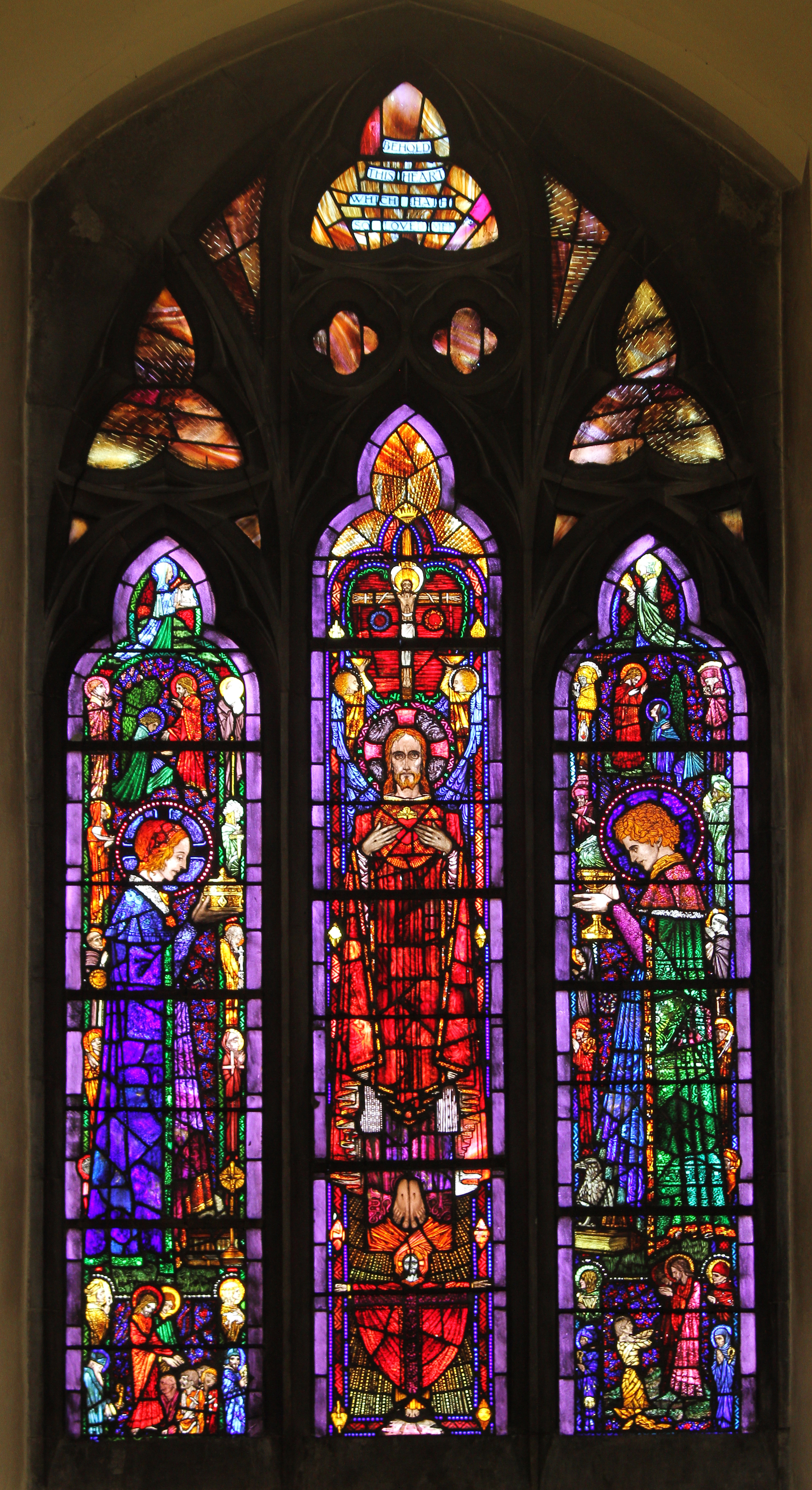

Mark Kelly (middle)

Before departing for the front, uniformed men flocked to have their photograph taken as a memento for their loved ones. Later, for grieving relatives without a grave to visit, these images often became the focus of their mourning.

Mark Kelly was a draper’s porter in 1911, single and living at home, by 1918 he was a married man with two daughters, but he died that October, just weeks before the end of the War.

Joseph Loftus was an agricultural labourer in 1911, the middle child of a family of 7, by 1915, within a month of landing in Gallipoli, he was dead, and now lies in an unmarked grave, his only memorial a line on the Hellispoint Memorial,

William Ennis was a butcher’s messenger boy in 1911, living in Prussia Street, by 1915, he was dead, his name recorded on the PLOEGSTEERT MEMORIAL, panel 9. Three of the 30, directly, or through a relative, connected with Phibsborough and a fraction of approximately 30,000 Irishmen (estimates vary) who died in the Great War.

Alongside them are those who died were those who returned, maimed in body or in spirit, to rebuild their lives in the new and desperately poor Ireland. Many never succeeded and carried the horror of the trenches to their deaths. These pains of war continued to effect more than those who fought and survived, woman and orphans made vulnerable in a patriarchal society by the loss of a breadwinner, and the families of returned, damaged survivors also suffered. Gay Byrne says his abiding memory of growing up on Rialto Street was his father, a surviver of Ypres, waking, screaming, in the middle of the night – terror that his son believes was caused by the trauma of the war. Irish Families continued to live the Great War long after the guns became silent on Armistice Day 1918.

In my own family there are gaps, poignant rather than traumatic. Joseph Loftus, my namesake, was my grandfather’s first cousin. Yet never in my childhood, did anyone ever observe that I shared a name with a relative who died in Gallipoli. His name returned to conversation in a family tree project and it seemed so sad, that this farm boy, who probably joined up for “a bit of adventure” could end up a forgotten statistic in Churchill’s failed “push” to Istanbul. In 2015, around the anniversary of his death, I went on pilgrimage to where he is name is carved, and found the ridge where he probably died, and where his unmarked remains have long since returned to the dust from whence they came. Moved that one so young could be completely lost from the family story, on returning home, I gave each of the “grandchildren” a memento to ensure that the next generation at least would know they had someone to be remembered from the War to end Wars. Hardly in the same league as a father’s night terrors, of course, but the legacy of the 1914-18 conflict has impacted choices of mine a full century later.

The Haunting Soldier,

St Stephen’s Green Dublin November 2018

These stories of those effected by the War, casualties, survivors and their families were lost from our collective memory, because in the decades after 1918, recalling them didn’t fit; public mourning for those who fought in the oppressor’s army was an embarrassment, and even, to some, an insult. But these men left behind wives, children, sweethearts and parents who, even in the newly created Free State still needed to grieve. Remembrance Day was a hugely important event in Dublin, attended by large crowds. Over time, vociferous objections and public order issues resulted in the disappearance of Remembrance Sunday from the public rituals of the republic. But the grief of so many mourners could not be buried so easily and mourners continued to carry their sadness in private, without the crumb of comfort that those across the Irish Sea could derive from the collective, poignant, remembering of the annual November ceremonies.

100 years later, on this anniversary at least, it is right to restore these men and their families to our public consciousness thankful that to do so is no longer to express an inconvenient grief. The world order has totally been remade, Ireland is no longer defined by liberation from an Empire that no longer exists, and remembering those slaughtered in a dreadful war cannot detract from our identity as a proud and independent nation or the honour we give to those who died creating it. In the public recalling of relatives who died, we are not at any level, nostalgically pinning for the political order that facilitated their deaths, but simply remembering the individuals themselves, praying for their souls and asking God to spare us for ever a repeat of the dreadful carnage that took their lives. We are remembering those left widowed or orphaned or those who relived the trenches in a husband’s or father’s trauma. At this remove, they too -most now themselves dead, deserve to be remembered as part of our commemoration of the terrible tragedy of the War to end Wars.

May their Souls, and the Souls of all the Faithful departed dead in War

through the mercy of God, rest in peace Amen

The names of many of those who died in the Great War from the Phibsborough area,

(or are relatives of current residents ) is available here .